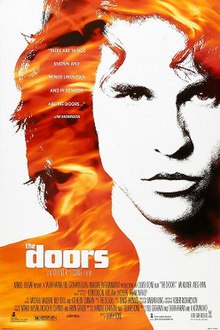

The Doors (film)

| The Doors | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

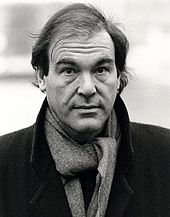

| Directed by | Oliver Stone |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | The Doors |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Tri-Star Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 141 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $32 million |

| Box office | $34.4 million (US/Canada)[1] |

The Doors is a 1991 American biographical film directed by Oliver Stone and written by Stone and Randall Jahnson. It is based on the history of American rock band the Doors and their influence on music and counterculture. The film stars Val Kilmer as singer Jim Morrison, Meg Ryan as Morrison's girlfriend Pamela Courson, Kyle MacLachlan as keyboardist Ray Manzarek, Frank Whaley as lead guitarist Robby Krieger, Kevin Dillon as drummer John Densmore, Billy Idol as Cat, and Kathleen Quinlan as journalist Patricia Kennealy.

The film portrays Morrison as a larger-than-life icon of 1960s rock and roll and counterculture, including portrayals of Morrison's recreational drug use, free love, hippie lifestyle, alcoholism, interest in hallucinogenic drugs as entheogens, and his growing obsession with death, presented as threads which weave in and out of the film.

Released by Tri-Star Pictures on March 1, 1991, The Doors grossed $34 million in the United States and Canada on a $32 million production budget. The film received mixed reviews from critics; while Kilmer's performance, the supporting cast, the cinematography, the production design and Stone's directing were praised, criticism was centered on its historical inaccuracy and depiction of Morrison.

Plot

[edit]In 1949, young Jim Morrison and his family are traveling on a desert highway in New Mexico where they encounter an auto wreck and see an elderly Native American dying by the roadside. In 1965, Jim arrives in California and is assimilated into the Venice Beach culture. During his tenure studying at UCLA, he meets Pamela Courson and they fall in love, becoming a couple. He also meets Ray Manzarek for the first time, as well as Robby Krieger and John Densmore, who form the Doors with Morrison.

Jim convinces his bandmates to travel to Death Valley and experience the effects of psychedelic drugs. Returning to Los Angeles, they play several shows at the famous Whisky a Go Go nightclub and develop a rabid fanbase. Jim's onstage antics and lewd performance of the group's song "The End" upset the club's owners, and the band is ejected from the venue. After the show, they are approached by producer Paul A. Rothchild and Jac Holzman of Elektra Records and are offered a deal to record their first album. The Doors are soon invited to perform on The Ed Sullivan Show, only to be told by one of the producers that they must change the lyric "girl we couldn't get much higher" in the song "Light My Fire", due to a reference to drugs. Despite this, Morrison performs the original lyric during the live broadcast and the band is not allowed to perform on the show again.

As the Doors' success continues, Jim becomes increasingly infatuated with his own image as "The Lizard King" and develops an addiction to alcohol and drugs. Jim becomes intimate with rock journalist Patricia Kennealy, who involves him in her witchcraft activities, participating in a mystical handfasting ceremony. Meanwhile, an elder spirit watches these events.

The rest of the band grows weary of Jim's missed recording sessions and absences at concerts. Jim arrives late and intoxicated to a Miami, Florida concert, becoming increasingly confrontational towards the audience and threatening to expose himself onstage. The incident is a low point for the band, resulting in criminal charges against Jim, cancellations of shows, breakdowns in Jim's personal relationships, and resentment from the other band members.

In 1970, following a lengthy trial, Jim is found guilty of indecent exposure and ordered to serve time in prison. However, he is allowed to remain free on bail, pending the results of an appeal. Patricia tells Jim that she is pregnant with his child, but Jim convinces her to have an abortion. Jim visits his bandmates for the final time, attending a birthday party hosted by Ray where he wishes the band luck in their future endeavors and gives each of them a copy of his poetry book An American Prayer. As Jim plays in the front garden with the children, he sees that one of them is his childhood self and comments, "This is the strangest life I've ever known" (a lyric from the Doors song "Waiting for the Sun"), before passing out.

In 1971, Jim and Pam move to Paris, France, to escape the pressures of the L.A. lifestyle. On the evening of July 3, Pam finds Jim dead in the bathtub of their apartment. He is buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery, besides other famous figures as Oscar Wilde, Marcel Proust and Moliere. Pam also dies three years later at the age of 27.

Cast

[edit]- Val Kilmer as Jim Morrison

- Sean Stone as young Jim

- Kevin Dillon as John Densmore

- Kyle MacLachlan as Ray Manzarek

- Kathleen Quinlan as Patricia Kennealy

- Meg Ryan as Pamela Courson

- Frank Whaley as Robby Krieger

- Josh Evans as Bill Siddons

- Crispin Glover as Andy Warhol

- Kelly Hu as Dorothy

- Dennis Burkley as Dog

- John Capodice as Jerry

- Billy Idol as Cat

- Patricia Kennealy-Morrison as Celtic Pagan priestess

- Michael Madsen as Tom Baker

- Costas Mandylor as Italian Count

- Debi Mazar as Whiskey girl

- Mimi Rogers as Gloria Stavers, magazine photographer

- Jennifer Rubin as Edie Sedgwick

- Jerry Sturm and Gretchen Becker as Mr. and Mrs. Morrison

- Floyd Westerman as a Native American Spirit

- Paul Williams as Warhol PR agent

- Christina Fulton as Nico

- Michael Wincott as Paul A. Rothchild

- Mark Moses as Jac Holzman

- Eric Burdon in a cameo appearance in the London Fog

- Paul A. Rothchild in a cameo appearance in the London Fog

- Sky Saxon in a cameo appearance in the Whisky a Go Go

- Oliver Stone as UCLA film professor

- Bruce MacVittie as UCLA Student

- Peter Crombie as Associate Lawyer

- Charlie Spradling as CBS Girl Backstage

- John Densmore as John Haeny, studio engineer

- William Kunstler as Jim's lawyer

- Josie Bissett as Robby Krieger's Girlfriend

- Wes Studi as Indian in Desert

- Titus Welliver as Macing Cop

Additionally Jennifer Tilly played the part of Okie girl but her scenes were deleted from the final film.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Film directors Quentin Tarantino,[2] Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese and William Friedkin had all flirted with making a Doors biopic over the years.[3] In 1985, Columbia Pictures acquired the rights from the Doors and the Morrison estate to make a film. Producer Sasha Harari wanted filmmaker Oliver Stone to write the screenplay but never heard back from his agent. After two unsatisfactory scripts were produced, Imagine Films replaced Columbia. Harari contacted Stone again and the director met with the surviving band members, telling them he wanted to keep a particularly wild scene from one of the early drafts. The group was offended by this and exercised their right of approval over the director, rejecting Stone.[citation needed]

By 1989, Mario Kassar and Andrew Vajna, who owned Carolco Pictures, had acquired the rights to the project and wanted Stone to direct it.[3] The Doors had seen Stone's film Platoon (1986) and were impressed with what he had done,[4] and Stone agreed to make the film after his next project, Evita. After spending years working on Evita and courting both Madonna and Meryl Streep to play the titular role, the film fell apart over salary negotiations with Streep and Stone quickly moved into pre-production for The Doors.[4]

Guitarist Robby Krieger had always opposed a Doors biopic until Stone signed on to direct.[5] Conversely, keyboardist Ray Manzarek had traditionally been the biggest advocate of immortalizing the band on film but opposed Stone's involvement.[5] He was not happy with the direction that Stone was going to take with the film and refused to give his approval. According to actor Kyle MacLachlan, "I know that he and Oliver weren't speaking. I think it was hard for Ray, he being the keeper of the Doors myth for so long".[6] According to Krieger, "when the Doors broke up Ray had his idea of how the band should be portrayed and John and I had ours".[5] Manzarek stated that he was not asked to consult on the film and wanted it to be about all four band members equally, rather than the focus being on Morrison.[7] Conversely, Stone stated that he repeatedly tried to get Manzarek involved, but "all he did was rave and shout. He went on for three hours about his point of view ... I didn't want Ray to be dominant, but Ray thought he knew better than anybody else".[8] Krieger claimed in his book Set the Night on Fire that Manzarek was also jealous of Stone because he wanted to direct the film himself.[9]

Screenplay

[edit]Stone first heard the Doors in 1967, when he was a 21-year-old soldier in Vietnam.[10] Before filming started, Stone and his producers had to negotiate with the three surviving band members and their label, Elektra Records, as well as the parents of both Morrison and his girlfriend Pamela Courson. Morrison's parents would only allow themselves to be depicted in a dream-like flashback sequence at the beginning of the film. The Coursons wanted there to be no suggestion in any way that Pamela caused Morrison's death. Stone found the Coursons the most difficult to deal with because they wanted Pamela to be portrayed as "an angel".[10] While researching the film, Stone read through transcripts of interviews with over 100 people.[11] Stone finally penned the film script in the summer of 1989, later stating that "The Doors script was always problematic. Even when we shot, but the music helped fuse it together".[12] Stone first picked the songs he wanted to use and then wrote "each piece of the movie as a mood to fit that song".[12] The Coursons did not like Stone's script and tried to slow the production down by refusing to allow any of Morrison's later poetry to be used in the film. (When Morrison died, Courson acquired the rights to Morrison's poetry; when she died, her parents got the rights.)[12]

Casting

[edit]For nearly 10 years prior to production, the project went through development hell after being considered by many studios and directors. Several actors, including Tom Cruise, Johnny Depp, John Travolta and Richard Gere, were each considered for the role of Morrison when the project was still in development in the 1980s,[13] with Bono of U2 and Michael Hutchence of INXS also expressing interest in the role. Stone initially offered the role to Ian Astbury of the Cult, who declined the role because he was not happy with the way Morrison was going to be represented in the film.[3]

When Stone began talking about the project in 1988, he had Val Kilmer in mind to play Morrison, after seeing him in the Ron Howard fantasy film Willow.[10][14] Kilmer had the same kind of singing voice as Morrison and, to convince Stone that he was right for the role, spent several thousand dollars of his own money and made his own eight-minute audition video, singing and looking like Morrison at various stages of his life.[15] To prepare for the role, Kilmer lost weight and spent six months rehearsing Doors songs every day; the actor learned 50 songs, 15 of which are actually performed in the film. Kilmer also spent hundreds of hours with the Doors' producer Paul A. Rothchild, who related "anecdotes, stories, tragic moments, humorous moments, how Jim thought ... interpretation of Jim's lyrics".[15] Rothchild also took Kilmer into the studio and helped him with "some pronunciations, idiomatic things that Jim would do that made the song sound like Jim".[15] Kilmer also met with Krieger and Densmore but Manzarek refused to talk to him.[15] When the Doors heard Kilmer singing they could not tell whether the voice was Kilmer's or Morrison's.[16]

Stone auditioned approximately 60 actresses for the role of Pamela Courson.[17] The role required nudity and the script featured sex scenes, which generated a fair amount of controversy. Casting director Risa Bramon felt that Patricia Arquette auditioned very well and should have gotten the role.[17] To prepare for the role, Meg Ryan talked to the Coursons and people that knew Pamela.[10] Before doing the film, she was not familiar with Morrison and "liked a few songs", adding, "I had to reexamine all my beliefs about [the 1960s] in order to do this movie".[18] In doing research, she also encountered several conflicting views of Pamela.[17]

Krieger acted as a technical advisor on the film, chiefly to show his cinematic alter ego, Frank Whaley, where to put his fingers on the guitar fretboard during the mimed performance sequences.[5] Similarly, Densmore also acted as a consultant on the film, tutoring Kevin Dillon.[13]

Principal photography

[edit]With a budget set at $32 million, The Doors was filmed over 13 weeks, predominantly in and around Los Angeles, California; Paris, France; New York City, New York; and the Mojave Desert.[7][19] Stone originally hired Paula Abdul to choreograph the film's concert scenes. She dropped out of the project because she did not understand Morrison's on-stage actions and was not familiar with the time period. Abdul recommended Bill and Jacqui Landrum, who watched hours of concert footage before working with Kilmer and got him to do dance exercises to loosen up his upper body and jumping routines to develop his stamina.[20]

During the concert scenes, Kilmer did his own singing, performing over the Doors' master tapes without Morrison's lead vocals, avoiding lip-synching.[21] Kilmer's endurance was put to the test during the concert sequences, which took several days to film, with Stone stating, "His voice would start to deteriorate after two or three takes. We had to take that into consideration."[22] One sequence, filmed inside the Whisky a Go Go, proved to be more difficult than others due to all the smoke and sweat, a result of the body heat and intense camera lights. "The End" sequence took five days to shoot, after which Kilmer was completely exhausted.[22]

Controversy arose during filming when a memo linked to Kilmer circulated among cast and crew members, listing rules of how the actor was to be treated for the duration of principal photography.[23] These provisions forbade people to approach him on set without good reason, address him by his own name while he was in character or stare at him on set. An upset Stone contacted Kilmer's agent and the actor claimed it was a misunderstanding and that the memo was for his own people and not the film crew.[23]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film contains over two dozen of the Doors' songs, although only half of these appear on the accompanying soundtrack album. In the film, original recordings of the band are combined with vocal performances by Kilmer himself,[24] although none of Kilmer's performances appear on the soundtrack album. In addition, two songs by the Velvet Underground ("Heroin" and "Venus in Furs") are heard throughout the film, with the former appearing on the soundtrack.[25]

Historicity

[edit]It's not Jim Morrison. It's Oliver Stone in leather pants.

The film is based mostly on real people and actual events, with some segments reflecting Stone's vision and dramatization of those people and events.[27] For example, when Morrison is asked to change the lyric in "Light My Fire" for his appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, he is depicted as blatantly ignoring the request, defiantly shouting "higher! Yeah!" into the television camera.[28] However, during the actual broadcast, Morrison simply sang the vocal with the same emphasis as on the record. Morrison later said the inclusion of "higher" in the live version was an accident, and that he had meant to change the lyric but was so nervous about performing on live television that he forgot. Conversely, Ray Manzarek said the Doors only pretended to agree to the changing of words and deliberately played the song as they always had, albeit without any added emphasis on the offending words.[29]

Several acts of violence portrayed in the film are disputed: Morrison is depicted as locking Pamela Courson in a closet and setting it on fire;[30][31] having an argument with Courson at a Thanksgiving celebration, where they both threaten each other with a knife; and angrily throwing a television set at Manzarek for licensing the use of "Light My Fire" in a Buick television commercial.[32] Even though Manzarek was frank about Morrison's tendency to go into senseless rages,[33] participants in the film agree that none of these specific incidents occurred. Stone acknowledges in the DVD director's commentary that the Thanksgiving scene never actually took place, nor the scene when the band members travel to a desert where Morrison encourages them to take psychedelic drugs.[34]

Dialogue that took place between Morrison and Patricia Kennealy is misrepresented in scenes between Morrison and Pam Courson, with Courson speaking Kennealy's words. Courson is also depicted as saying hostile things to Kennealy, when by Kennealy's reports the interactions between the two women were polite.[35] Kennealy is also portrayed as being the girl Morrison was with in the shower stall backstage before the December 9, 1967 New Haven concert (not 1968 as inscribed in the film), when in fact he was with a local teenage co-ed from Southern Connecticut State University.[36] Additionally, the New Haven venue is presented in the film as an amphitheater with a large balcony and a packed audience, when in reality it was a rather decrepit, half-empty hockey rink with audience members sitting on folding wooden chairs. In the scene at a press conference set in New York City in 1967, when Kennealy is first introduced to Morrison, the singer is asked a question regarding "the dreadful reviews your new poetry book has got"; at that time, Morrison had not yet published any volumes of his poetry.[citation needed]

John Densmore is portrayed as hating Morrison when the singer's personal and drug problems begin to dominate his behavior. However, Densmore states in his biography Riders on the Storm that he never directly confronted Morrison about his drunken behavior.[37]

In the concert sequences naked women are shown prancing around onstage, which Densmore said did not happen at any of the Doors' concerts.[38] Krieger said that he did not take acid prior to the concert at the Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami on March 1, 1969 as depicted in the film.[39]

The surviving Doors members were all, to one degree or another, unhappy with the final film. In a 1991 interview with Gary James, Manzarek criticized Stone for exaggerating Morrison's alcohol consumption: "Jim with a bottle all the time. It was ridiculous ... It was not about Jim Morrison. It was about Jimbo Morrison, the drunk. God, where was the sensitive poet and the funny guy? The guy I knew was not on that screen."[40] In the afterword of his book Riders on the Storm, Densmore says that the movie is based on "the myth of Jim Morrison" and criticizes the film for portraying Morrison's ideas as "muddled through the haze of the drink [alcohol]".[41] In a 1994 interview, Krieger said that the film does not give the viewer "any kind of understanding of what made Jim Morrison tick". Krieger added, "They left a lot of stuff out. Some of it was overblown, but a lot of the stuff was very well done, I thought."[42]

In Manzarek's biography of the Doors, Light My Fire, he often criticizes Stone and his account of Morrison. For example, in Stone's re-creation of Morrison's student film at UCLA, Morrison watches a D-Day sequence on television and shouts profanities in German, with a near-nude German exchange student dancing on top of the television sporting a swastika armband. According to Manzarek, the only similarity between Stone's version and Morrison's was that the girl in question was German.[43][44] Manzarek described Stone's version as a "grotesque exaggeration", and recalled that Morrison's film was a "much lighter, much friendlier, much funnier kind of thing".[43]

As the credits point out and as Stone emphasizes in his DVD commentary, some characters, names, and incidents in the film are fictitious or amalgamations of real people.[34] In the 1997 documentary, The Road of Excess, Stone states that Quinlan's character, Patricia Kennealy, is a composite, and in retrospect should have been given a fictitious name.[45] Kennealy was hurt by her portrayal in the film and objected to a scene where Morrison states that he did not take their handfasting ceremony seriously. Kennealy is credited as a "Wiccan priestess" for her cameo role as the priestess who married the real Jim and Patricia, but the real priestess was a Celtic pagan.[46][47]

The former Doors said the depiction of Pamela Courson is not accurate at all, as their book The Doors describes this version of Courson as "a cartoon of a girlfriend".[48] Courson's parents had inherited Morrison's poems when their daughter died, and Stone had to agree to restrictions about his portrayal of her in exchange for the rights to use the poetry. In particular, Stone agreed to avoid any suggestion that Courson may have been responsible for Morrison's death.[49] However, Alain Ronay and Courson herself had both said that she was responsible. In Riders on the Storm, Densmore says Courson said she felt terribly guilty because she had obtained drugs that she believed had either caused or contributed to Morrison's death.[50]

Release and reception

[edit]The Doors was entered into the 17th Moscow International Film Festival.[51] In April 2019, a restored version of the film was selected to be shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival.[52]

In a contemporary review, Roger Ebert gave The Doors two-and-a-half out of four stars. Ebert wrote that he couldn't be invested too much to the film's story, but praised the acting performances, particularly Kilmer's.[53] Contrarily, Rolling Stone wrote a glowing review, rating it with four out of four stars.[54] In a 2010 piece for Q magazine, Keith Cameron stated that "few people emerged from seeing the film having raised their opinions of that band and especially its singer Jim Morrison." The problem, as critic Cameron put it, was not so much that "Stone dwelled upon Morrison the inebriate, the philanderer, or the pretentious Lizard King", but rather the "clichéd Hollywood devices for sucking the wonder from the pioneering band: actors with fake hair saying silly things ..." and "a self-important director's turgid attempts to make grand statements about America."[55]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 56% approval rating based on 61 reviews and an average rating of 5.90/10. The site's consensus states: "Val Kilmer delivers a powerhouse performance as one of rock's most incendiary figures, but unfortunately, Oliver Stone is unable to shed much light on the circus surrounding the star."[56] Metacritic reports a 62 out of 100 rating, based on 19 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[57]

Home media and The Final Cut

[edit]The Doors was released on DVD in 1997 and again on August 14, 2001[58] and was later released on Blu-ray on August 12, 2008.[58] The film was released on 4K Blu-ray on July 23, 2019, with a new version of the film dubbed The Final Cut. Supervised by Stone, it features remastered sound and removes a scene where Morrison, following his trial, almost commits suicide.[59] Stone later noted that he had cut 3 minutes for The Final Cut as he initially felt the film was too long but shortly after realised he had made a mistake as it left unanswered questions. He has said he prefers the theatrical version and wanted to ensure that version is available on home media.[60]

See also

[edit]- List of films featuring hallucinogens

- When You're Strange – a 2009 documentary film about The Doors

References

[edit]- ^ The Doors at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Bose, Swapnil Dhruv (January 27, 2022). "Val Kilmer Explains How He Prepared to Play the Role of Jim Morrison". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c Riordan 1996, p. 308.

- ^ a b Riordan 1996, p. 310.

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Justin (December 28, 1990). "Opening Up a Closed Door". St. Petersburg Times. p. 19.

- ^ MacInnis, Craig (March 2, 1991). "The Myth is Huge, but the Truth is the Lure of the Eternal". Toronto Star. pp. H1.

- ^ a b Broeske, P (March 10, 1991). "Stormy Rider". Sunday Herald.

- ^ Riordan 1996, p. 312.

- ^ Krieger 2021, pp. 287–288.

- ^ a b c d McDonnell, D. (March 2, 1991). "Legendary Rocker Lives Again". Herald Sun. p. 27.

- ^ "Oliver Stone and The Doors". The Economist. March 16, 1991.

- ^ a b c Riordan 1996, p. 311.

- ^ a b McDonnell, D. (March 16, 1991). "Rider on the Storm". The Courier-Mail.

- ^ Green, Tom (March 4, 1991). "Kilmer's Uncanny Portrait of Morrison Opens Career Doors". USA Today. pp. 4D.

- ^ a b c d Hall, Carla (March 3, 1991). "Val Kilmer, Lighting the Fire". Washington Post. pp. G1.

- ^ Riordan 1996, p. 314.

- ^ a b c Riordan 1996, p. 316.

- ^ Riordan 1996, p. 322.

- ^ Riordan 1996, p. 317.

- ^ Thomas, Karen (March 12, 1991). "Helping Stage The Doors". USA Today. pp. 2D.

- ^ Riordan 1996, p. 318.

- ^ a b Kilday, Gregg (March 1, 1991). "Love Me Two Times". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 24, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ^ a b Riordan 1996, p. 326.

- ^ Burwick, Kevin (June 14, 2017). "Val Kilmer Shares Rare Doors Movie Rehearsal Video". MovieWeb. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Doors". AllMusic. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Meek, Tom (April 5, 2010). "Interview: Ray Manzarek of the Doors". For What It's Worth. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Krieger 2021, p. 258.

- ^ Goldsmith, Willson & Fonseca 2016, p. 205.

- ^ Manzarek 1998, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Wheeler, Steven P. (April 10, 2017). "A Conversation with Frank Lisciandro". ROKRITR.com.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick (March 7, 1991). "Ray Manzarek Slams 'The Doors'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Chat with Ray Manzarek". November 17, 1997.

Jim burning up Pam in the closet never happened. Jim throwing a television set at Ray never happened! The car commercial on TV never happened. The big fight after Ray and Dorothy's wedding never happened etc.

- ^ Manzarek 1998, pp. 180, 205–207, 305–308.

- ^ a b Oliver Stone (1991). The Doors (DVD Audio Commentary). Lionsgate.

- ^ Kennealy, Patricia (August 1991). "The Movie: A Personal Review". The Doors Quarterly Magazine. Vol. 24.

- ^ Weidman 2011, p. 267.

- ^ Densmore 1991, p. 268.

- ^ Clash, Jim (January 25, 2015). "Doors Drummer John Densmore On Oliver Stone, Cream's Ginger Baker (Part 3)". Forbes. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (April 15, 1991). "Ex-Doors Disagree on Oliver Stone Film". Knight Ridder.

- ^ Interview with Ray Manzarek at Classic Bands

- ^ Densmore 1991, p. Afterword.

- ^ "Interview With Robby Krieger". Classicbands.com. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ a b Manzarek 1998, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Tunzelmann, Alex von (February 17, 2011). "Oliver Stone's The Doors: a flash in the pan that won't light anyone's fire". The Guardian. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Kiselyak, Charles (1997). The Road of Excess (documentary).

- ^ Kennealy, Patricia (1998). Blackmantle - A Book of The Keltiad. New York: HarperPrism. ISBN 0-06-105610-3.

- ^ Kennealy, Patricia (1993). Strange Days: My Life With And Without Jim Morrison. New York: Dutton/Penguin. pp. 169–180. ISBN 978-0-45226-981-1.

- ^ Fong-Torres & Doors 2006, p. 232.

- ^ Broeske, Pat H. (January 7, 1990). "Jim Morrison: Back to the Sixties Darkly". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Densmore 1991, p. [page needed].

- ^ "17th Moscow International Film Festival (1991)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 2014-04-03. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ^ "Cannes Classics 2019". Festival de Cannes. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 1, 1991). "The Doors". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ "The Doors" (review) Archived 2014-07-18 at archive.today Rolling Stone (March 1, 1991)

- ^ Cameron, Keith (October 2010). "Review Music DVDs. The Doors. When You're Strange". Q. p. 134.

- ^ "The Doors (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ "The Doors reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Doors DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- ^ "The Doors: The Final Cut - 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- ^ @TheOliverStone (February 5, 2024). "Note from Director to #TheDoors fans" (Tweet). Retrieved February 8, 2024 – via Twitter.

Bibliography

[edit]- Densmore, John (1991). Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and the Doors (1st ed.). New York City: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-385-30033-6.

- Fong-Torres, Ben; Doors, the (October 25, 2006). The Doors. Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-0303-7.

- Krieger, Robby (2021). Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying, and Playing Guitar with the Doors. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-0316243544.

- Manzarek, Ray (1998). Light My Fire: My Life with the Doors. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books. ISBN 978-0-425-17045-8.

- Riordan, James (September 1996). Stone: A Biography of Oliver Stone. New York: Aurum Pres. ISBN 1-85410-444-6.

- Goldsmith, Melissa U. D.; Willson, Paige A.; Fonseca, Anthony J. (October 7, 2016). The Encyclopedia of Musicians and Bands on Film. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442269873.

- Hopkins, Jerry; Sugerman, Danny (1980). No One Here Gets Out Alive. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-97133-1.

- Weidman, Richie (October 1, 2011). The Doors FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Kings of Acid Rock. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Welsh, James (2012). The Oliver Stone Encyclopedia. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810883529.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The Doors at IMDb

- The Doors at the TCM Movie Database

- The Doors at Box Office Mojo

- The Doors at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Doors at Metacritic

- The Road of Excess at IMDb, a documentary of The Doors, included with the 2001 DVD

- 1991 films

- 1991 comedy-drama films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s biographical drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s musical drama films

- American biographical drama films

- American musical drama films

- American rock music films

- Biographical films about musicians

- Carolco Pictures films

- Cultural depictions of Jim Morrison

- Cultural depictions of Andy Warhol

- Films about musical groups

- Films about death

- Films directed by Oliver Stone

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in the 1970s

- Films with screenplays by Oliver Stone

- Imagine Entertainment films

- Musical films based on actual events

- StudioCanal films

- TriStar Pictures films

- The Doors

- Films produced by Mario F. Kassar

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language comedy-drama films

- English-language musical drama films

- 1991 musical films