James Gillray

James Gillray | |

|---|---|

Charles Turner, James Gillray, 1819, mezzotint after Gillray's self-portrait, National Portrait Gallery, London | |

| Born | 13 August 1756[1][2] |

| Died | 1 June 1815 (aged 58) St James's, City and Liberty of Westminster, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | English |

| Occupations | Caricaturist, printmaker |

James Gillray (13 August 1756[1][2] – 1 June 1815) was a British caricaturist and printmaker famous for his etched political and social satires, mainly published between 1792 and 1810. Many of his works are held at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Gillray has been called "the father of the political cartoon", with his works satirizing George III, Napoleon, prime ministers and generals.[3] Regarded as one of the two most influential cartoonists, the other being William Hogarth, Gillray's wit and humour, knowledge of life, fertility of resource, keen sense of the ludicrous, and beauty of execution, at once gave him the first place among caricaturists.[3][4][5]

Early life

[edit]He was born in Chelsea, London. His father had served as a soldier: he lost an arm at the Battle of Fontenoy and was admitted, first as an inmate and subsequently as an outdoor pensioner, at Chelsea Hospital. Gillray commenced life by learning letter-engraving, at which he soon became adept. Finding this employment irksome, he then wandered for a time with a company of strolling players. After a chequered experience, he returned to London and was admitted as a student in the Royal Academy, supporting himself by engraving, and probably issuing a considerable number of caricatures under fictitious names.[6]

His caricatures are almost all in etching, some also with aquatint, and a few using stipple technique. None can correctly be described as engravings, although this term is often loosely used to describe them. Hogarth's works were the delight and study of his early years. Paddy on Horseback, which appeared in 1779, is the first caricature which is certainly his. Two caricatures on Admiral Rodney's naval victory at the Battle of the Saintes, issued in 1782, were among the first of the memorable series of his political sketches.[6][7]

Adult life

[edit]

The name of Gillray's publisher and print seller, Hannah Humphrey – whose shop was first at 227 Strand, then in New Bond Street, then in Old Bond Street, and finally in St James's Street – is inextricably associated with that of the caricaturist himself. Gillray lived with Miss (often called Mrs) Humphrey during the entire period of his fame. It is believed that he several times thought of marrying her, and that on one occasion the pair were on their way to the church, when Gillray said: "This is a foolish affair, methinks, Miss Humphrey. We live very comfortably together; we had better let well alone." There is no evidence, however, to support the stories which scandalmongers invented about their relationship.[6] One of Gillray's prints, "Twopenny Whist", is a depiction of four individuals playing cards, and the character shown second from the left, an ageing lady with eyeglasses and a bonnet, is widely believed to be an accurate depiction of Miss Humphrey.

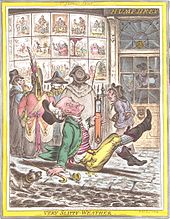

Gillray's plates were exposed in Humphrey's shop window, where eager crowds examined them.[6] One of his later prints, Very Slippy-Weather, shows Miss Humphrey's shop in St. James's Street in the background. In the shop window a number of Gillray's previously published prints, such as Tiddy-Doll the Great French Gingerbread Maker, Drawing Out a New Batch of Kings; His Man, Talley Mixing up the Dough, a satire on Napoleon's king-making proclivities, are shown in the shop window.

Gillray's eyesight began to fail in 1806. He began wearing spectacles but they were unsatisfactory. Unable to work to his previous high standards, James Gillray became depressed and started drinking heavily. He produced his last print in September 1809. As a result of his heavy drinking Gillray suffered from gout throughout his later life.

His last work, from a design by Bunbury, is entitled Interior of a Barber's Shop in Assize Time, and is dated 1811. While he was engaged on it he became mad, although he had occasional intervals of sanity, which he employed on his last work. The approach of madness may have been hastened by his intemperate habits.[6]

In July 1811 Gillray attempted to kill himself by jumping out of an attic window above Humphrey's shop in St James's Street. Gillray lapsed into insanity and was looked after by Hannah Humphrey until his death on 1 June 1815 in London; he was buried in St James's churchyard, Piccadilly.

The art of caricature

[edit]

A number of his most trenchant satires are directed against George III, who, after examining some of Gillray's sketches, said "I don't understand these caricatures." Gillray revenged himself for this utterance by his caricature entitled A Connoisseur Examining a Cooper, which he is doing by means of a candle on a "save-all", so that the sketch satirises at once the king's pretensions to knowledge of art and his miserly habits.[6]

During the French Revolution, Gillray took a conservative stance, and he issued caricature after caricature ridiculing the French and Napoleon (usually using Jacobin) and glorifying John Bull. A number of these were published in the Anti-Jacobin Review. He is not, however, to be thought of as a keen political adherent of either the Whig or the Tory party; his caricatures satirized members of all sides of the political spectrum.[6]

The times in which Gillray lived were peculiarly favourable to the growth of a great school of caricature. Party warfare was carried on with great vigour and not a little bitterness; and personalities were freely indulged in on both sides. Gillray's incomparable wit and humour, knowledge of life, fertility of resource, keen sense of the ludicrous, and beauty of execution, at once gave him the first place among caricaturists. He is distinguished in the history of caricature by the fact that his sketches are real works of art. The ideas embodied in some of them are sublime and poetically magnificent in their intensity of meaning, while the forthrightness — which some have called coarseness — which others display is characteristic of the general freedom of treatment common in all intellectual departments in the 18th century. The historical value of Gillray's work has been recognized by many discerning students of history. As has been well remarked: "Lord Stanhope has turned Gillray to account as a veracious reporter of speeches, as well as a suggestive illustrator of events."[4]

His contemporary political influence is borne witness to in a letter from Lord Bateman, dated 3 November 1798. "The Opposition", he writes to Gillray, "are as low as we can wish them. You have been of infinite service in lowering them, and making them ridiculous." Gillray's extraordinary industry may be inferred from the fact that nearly 1000 caricatures have been attributed to him; while some consider him the author of as many as 1600 or 1700. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, "Gillray is as invaluable to the student of English manners as to the political student, attacking the social follies of the time with scathing satire; and nothing escapes his notice, not even a trifling change of fashion in dress. The great tact Gillray displays in hitting on the ludicrous side of any subject is only equalled by the exquisite finish of his sketches—the finest of which reach an epic grandeur and Miltonic sublimity of conception."[4]

Gillray's caricatures are generally divided into two classes, the political series and the social, though it is important not to attribute to the term "series" any concept of continuity or completeness. The political caricatures comprise an important and invaluable component of the history extant of the latter part of the reign of George III. They were circulated not only in Britain but also throughout Europe, and exerted a powerful influence both in Britain and abroad. In the political prints, George III, George's wife Queen Charlotte, the Prince of Wales (later prince regent, then King George IV), Fox, Pitt the Younger, Burke and Napoleon Bonaparte are the most prominent figures.[4]

In 1788, appeared two fine caricatures by Gillray. Blood on Thunder fording the Red Sea represents Lord Thurlow carrying Warren Hastings through a sea of gore: Hastings looks very comfortable, and is carrying two large bags of money. Market-Day pictures the ministerialists of the time as cattle for sale.[4]

Among Gillray's best satires on George III are: Farmer George and his Wife, two companion plates, in one of which the king is toasting muffins for breakfast, and in the other the queen is frying sprats; The Anti-Saccharites, where the royal pair propose to dispense with sugar, to the great horror of the family; A Connoisseur Examining a Cooper; the paired plates A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion and Temperance enjoying a Frugal Meal, satirising the excesses of the Prince Regent (later George IV of the United Kingdom) and the miserliness of his father, George III of the United Kingdom respectively; Royal Affability; A Lesson in Apple Dumplings; and The Pigs Possessed.[4]

Other political caricatures include: Britannia between Scylla and Charybdis, a picture in which Pitt, so often Gillray's butt, figures in a favourable light; The Bridal Night; The Apotheosis of Hoche, which concentrates the excesses of the French Revolution in one view; The Nursery with Britannia reposing in Peace; The First Kiss these Ten Years (1803), another satire on the peace, which is said to have greatly amused Napoleon; The Hand-Writing upon the Wall; The Confederated Coalition, a swipe at the coalition which superseded the Addington ministry; Uncorking Old Sherry; The Plumb-pudding in danger (probably the best known political print ever published); Making Decent; Comforts of a Bed of Roses; View of the Hustings in Covent Garden; Phaethon Alarmed; and Pandora opening her Box.[4]

As well as being blatant in his observations, Gillray could be incredibly subtle, and puncture vanity with a remarkably deft approach. The outstanding example of this is his print Fashionable Contrasts;—or—The Duchess's little Shoe yeilding [sic] to the Magnitude of the Duke's Foot. This was a devastating image aimed at the ridiculous sycophancy directed by the press towards Frederica Charlotte Ulrica, Duchess of York, and the supposed daintiness of her feet. The print showed only the feet and ankles of the Duke and Duchess of York, in an obviously copulatory position, with the Duke's feet enlarged and the Duchess's feet drawn very small. This print silenced forever the sycophancy of the press regarding the union of the Duke and Duchess.

The miscellaneous series of caricatures, although they have scarcely the historical importance of the political series, are more readily intelligible, and are even more amusing. Among the finest are: Shakespeare Sacrificed; Two-Penny Whist (which features an image of Hannah Humphrey); Oh that this too solid flesh would melt; Sandwich-Carrots; The Gout; Comfort to the Corns; Begone Dull Care; The Cow-Pock, which gives humorous expression to the popular dread of vaccination; Dilletanti Theatricals; and Harmony before Matrimony and Matrimonial Harmonics—two sketches in violent contrast to each other.[4]

-

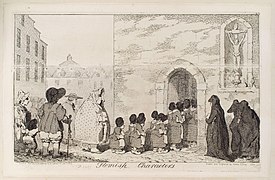

Flemish Characters (1793), published by G. Humphrey, 27 St James's Street, 1 January 1822

-

Flemish Characters, published by G. Humphrey, 27 St James's Street, 1 January 1822

Famous editions

[edit]A selection of Gillray's works appeared in James Gillray: The Caricatures printed between 1818 and the mid-1820s and published by John Miller, Bridge Street and W. Blackwood, Edinburgh. Nine parts were released. The next edition was Thomas McLean's, which was published with a key, in 1830.

In 1851 Henry George Bohn put out an edition, from the original plates in a handsome elephant folio, with coarser sketches—commonly known as the "Suppressed Plates"—being published in a separate volume. For this edition Thomas Wright and Robert Harding Evans wrote a commentary, a history of the times embraced by the caricatures. Many copies of the Bohn Edition have been broken up into individual sheets and passed off as originals (see Collecting below). Although the two volumes of the Bohn Edition are often represented as being a complete collection of Gillray's works, this is not the case: for example, Doublûres of Characters is not included in either volume. This is most likely because this print was not published by Hannah Humphrey, but by John Wright for the Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine.

The next edition, entitled The Works of James Gillray, the Caricaturist: with the Story of his Life and Times (Chatto & Windus, 1874), was the work of Thomas Wright,[10] and introduced Gillray to larger public. This edition, which is complete in one volume, contains two portraits of Gillray, and upwards of 400 illustrations.[4]

Gallery

[edit]-

The American Rattle Snake (1782)

-

Light expelling Darkness,—Evaporation of Stygian Exhalations,—or—The Sun of the Constitution, rising superior to the Clouds of Opposition (1795)

-

Fashionable Contrasts;—or—The Duchess's little Shoe yeilding [sic] to the Magnitude of the Duke's Foot (1792)

-

Following the Fashion — Short-bodied gowns, a Neo-Classical trend in women's clothing styles (1794)

-

A Burgess of Warwick Lane — John Burges, on tiptoe outside a building in Warwick Lane (1795)

-

The Whore's Last Shift (1779)

-

A noble lord, on an approaching peace, too busy to attend to the expenditure of a million of the public money

-

Siege de la Colonee de Pompée — A group of French savants huddle together at the top of a column

-

The Dissolution — Pitt as an alchemist, using a crown-shaped bellows to blow the flames

-

Regardez moi ("Look at me")

-

National Conveniences, published by Hannah Humphrey 25 January 1796

-

Uncorking Old Sherry (1805)

-

Hand-coloured etching depicting the use of Perkins' tractors

-

The Spanish Bullfight, 1808

-

The Hand-Writing upon the Wall.

Influence

[edit]Gillray is still revered as one of the most influential political caricaturists of all time, and among the leading cartoonists on the political stage in the United Kingdom today, both Steve Bell and Martin Rowson acknowledge him as probably the most influential of all their predecessors in that particular arena [citation needed]. Professor David Taylor, a University of Toronto expert in political satire, stated in 2013, "Without question, if the leading cartoonist back then—James Gillray—had depicted Rob Ford he would have been far more merciless than they are today."[11]

Regarded as being one of the two most influential cartoonists, the other being William Hogarth, Gillray has been called the father of the political cartoon.[3] The 20th-century New Zealander cartoonist David Low described Hogarth as the grandfather and Gillray the father of the political cartoon.[3] The face of Court Flunkey from the 1980s/1990s British television satirical puppet show Spitting Image is a caricature of Gillray, intended as a homage to the father of political cartooning.[12]

In the article titled A Rousseauian Reading of Gillray's National Conveniences John Moores wrote, "As National Conveniences and The Fashionable Mamma show, Gillray was interested in the ideas of Rousseau, his work was influenced by them, and, as later designs on revolution and radicalism indicate, he held Rousseau in higher regard than other revolutionary influences, using a Rousseauian technique of misspelling to place uncertainty in his depictions of Rousseau's texts."[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gillray, James and Draper Hill (1966). Fashionable contrasts. Phaidon. p. 8.

- ^ a b Baptism register for Fetter Lane (Moravian) confirms birth as 13 August 1756, baptism 17 August 1756

- ^ a b c d "Satire, sewers and statesmen: why James Gillray was king of the cartoon". The Guardian. 16 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chisholm 1911, p. 24.

- ^ "James Gillray: The Scourge of Napoleon". HistoryToday.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chisholm 1911, p. 23.

- ^ "'Rodney invested – or – Admiral Pig on a cruize' (George Bridges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney; Hugh Pigot; Charles James Fox)". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Wright T, Evans RH (1851). Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray: Comprising a Political and Humorous History of the Latter Part of the Reign of George the Third. London: Henry G. Bohn. p. ix. OCLC 59510372.

- ^ Martin Rowson, speaking on The Secret of Drawing, presented by Andrew Graham Dixon, BBCTV

- ^ "Review of The Works of James Gillray by Thomas Wright". The Quarterly Review. 136: 453–497. April 1874.

- ^ "18th-century cartoonists—who might have loved Rob Ford—among Polanyi Prize-winning subjects". Toronto Star. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ "James Gillray". lambiek.net. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016.

- ^ Moores, John (1 March 2013). "A Rousseauian Reading of Gillray's National Conveniences". European Comic Art. 6 (1): 129–155. doi:10.3167/eca.2013.060107. ISSN 1754-3797.

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gillray, James". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 23–24.

Further reading

[edit]- Clayton, Tim. "James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire" Yale University Press (2022)

- Haywood, Ian. "'The dark sketches of a revolution': Gillray, the Anti-Jacobin Review, and the Aesthetics of Conspiracy in the 1790s". European Romantic Review 22.4 (2011): 431–451.

- Haywood, Ian. "The Transformation of Caricature: A Reading of Gillray's The Liberty of the Subject". Eighteenth-Century Studies 43.2 (2010): 223–242. online

- Hill, Draper. Mr. Gillray: The Caricaturist, a Biography (Phaidon Publishers Incorporated, distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1965).

- Loussouarn, Sophie. "Gillray and the French Revolution". National Identities (Sept 2016) 18#3 pp 327–343.

- Patten, Robert L. "Conventions of Georgian Caricature". Art Journal 43.4 (1983): 331–338.

- Price, Chris. "'Pictorially Speaking, so Ludicrous': George IV on the Dance Floor", Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography XLIII/1–2 (2018), 49–65.

Primary sources

[edit]- Gillray, James. The Satirical Etchings of James Gillray (Dover Publications, 1976), black-and-white reproductions.

External links

[edit]- James Gillray Gallery at MuseumSyndicate

- GreatCaricatures.com: James Gillray Galleries

- James Gillray at The National Portrait Gallery (United Kingdom).

- James Gillray and James Gillray: The Art of Caricature at The Tate Britain.

- "Images related to James Gillray". NYPL Digital Gallery.

- James Gillray prints Archived 29 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the Lewis Walpole Library of Yale University.

- University of Nottingham Visual Resources – James Gillray cartoons

- Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray by Thomas Wright, R. H. Evans

- Princeton University. Gillray Collection

- James Gillray: Caricaturist [1]

- Works by James Gillray in the Robinson Collection of Caricatures at the Library of Trinity College Dublin, digitised here

- Exhibition Drawing Your Attention: Four Centuries of Political Caricatures by the Library of Trinity College Dublin

![Fashionable Contrasts;—or—The Duchess's little Shoe yeilding [sic] to the Magnitude of the Duke's Foot (1792)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/Fashionable_contrasts_james_gillray.jpg/422px-Fashionable_contrasts_james_gillray.jpg)